When people ask me if I like comic books I always have a split-second reaction. The answer is no. But it’s a nuanced no. I don’t like superhero comic books, but I grew up reading plenty of other stuff.

While in the United States “comic book” can be read as a synonym for “superhero,” such a correlation has not traditionally existed in Mexico. Mexican artists during their Golden Age were more interested in other kinds of content. This doesn’t mean there weren’t any superheroes—Fantomas, El Santo and Kalimán come to mind—but you were more likely to find other sorts of local comic books. And when people thought comic books, they probably thought historietas, monitos, una de vaqueros, all of which conjure something very far from Superman, Batman or the X-Men.

For many decades Mexico didn’t have comic book shops and all comics were sold at the newsstands, many of the most popular ones in pocket-sized formats. The buyer of these trinkets were not only children, but often adults from the lower classes. This changed somewhat in the 1960s, with the development of more political, ambitious fare such as Los Supermachos, but comic books were considered, culturally, the bottom of the barrel. As you can guess judging by these descriptions, Mexican comics did not face the censorship issues American creators struggled with. There was no Comics Code Authority. This doesn’t mean people were not disturbed by the content of certain comic books. Starting in the 1940s, the Catholic Mexican Legion of Decency and the Union of Mexican Catholics began campaigning against the pepines (comics).

Eventually, the Mexican government targeted “indecent illustrations” through the Comisión Calificadora de Publicaciones y Revistas Ilustradas beginning in 1944. But though in theory any comic which denigrated good work ethics, democracy, the Mexican people and culture, utilized slang or lowered moral standards could be banned, the Commission simply did not have enough resources to accomplish much. Sometimes the Commission might threaten a title or publisher, even levy fines, but the comics quickly appeared under a new name. It was like a game of whack-a-mole.

Mexican comic books were also allowed to exist uncontested due to nationalist fears. The Mexican government was worried about a possible Americanization and loss of Mexican values, and therefore it viewed local comic production as a positive development. That the lurid comics did not really attack the status quo, nor engaged in political attacks, also lulled the government into a feeling that such entertainment was fine.

Buy the Book

Mexican Gothic

Mexican comic creators benefited from subsidies provided via Productora e Importadora de Papel, Sociedad Autónoma. PIPSA controlled the supply of paper in Mexico and ensured comic book publishers could obtain cheap printing materials. This in turn meant comic books were an easily accessible product for the poor and working-class, and it gave birth to a Golden Age of Comic Books from the ’40s to the ’60s.

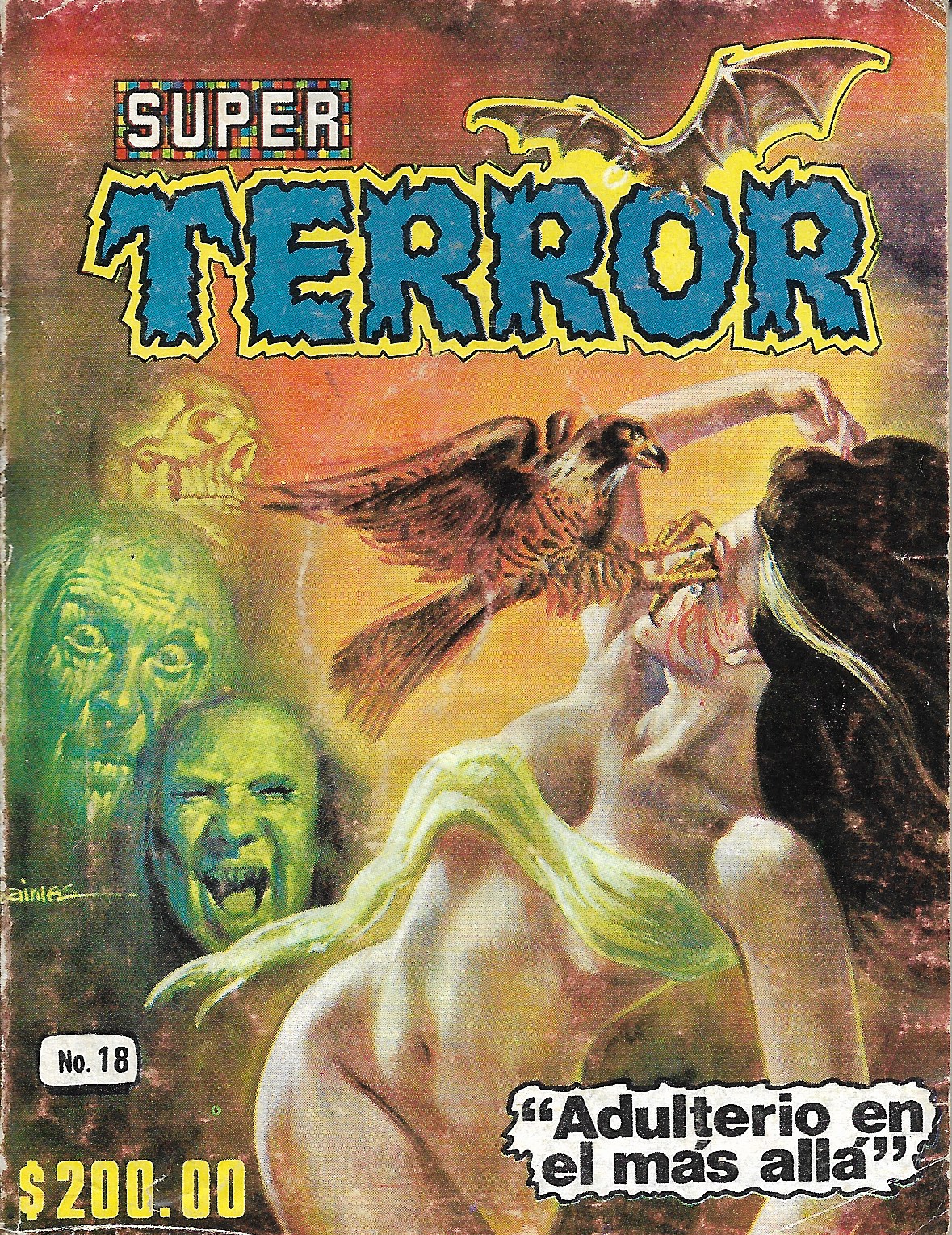

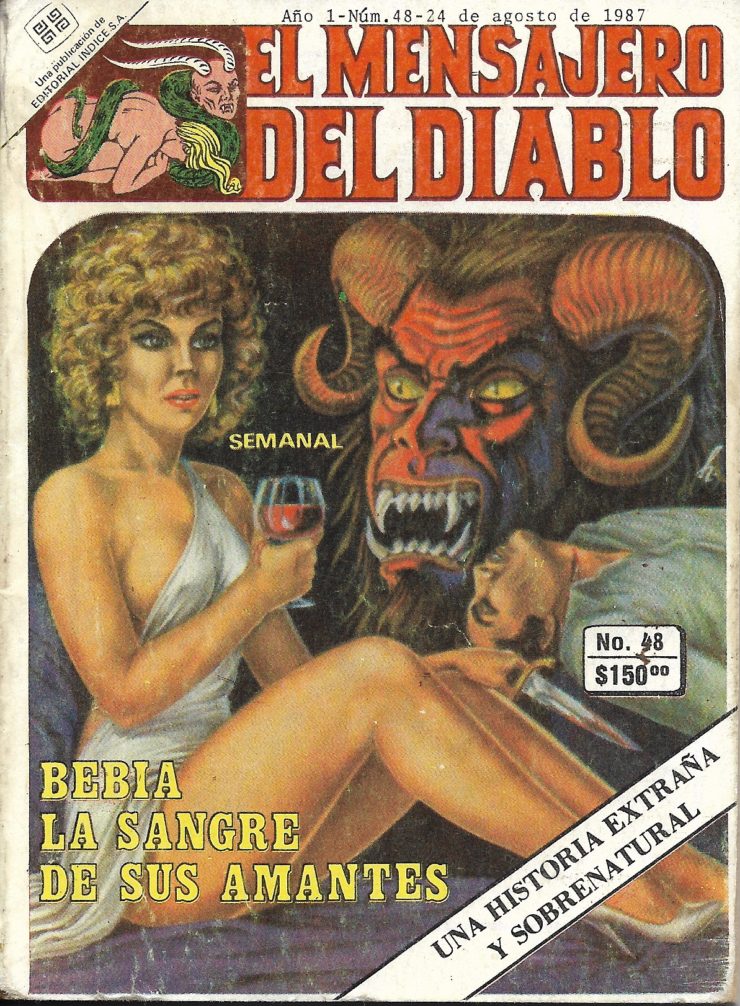

By the 1960s, there were hundreds of comics published each week in Mexico City, which remained the printing capital and cultural center for the comic boom. Chief among the comics were Westerns, humor comic books, romances and increasingly exploitation comics featuring nudity, slurs and violence. Therefore, the newsstand was a study in contrasts. On the one hand you had the drama of the romances—many of which were later adapted into soap operas—and then you had the cheap, saucy comics meant for men.

Among this eclectic mix of modern Cinderellas looking for love and nymphomaniacs wanting to party, there were some horror comic books. They all tended to stick to an anthology format, with one or two tales concluding in each issue instead of following a long storyline. The horror comics were all hand drawn, but other genres, especially the erotic titles, employed photos to tell stories in a format called fotonovela.

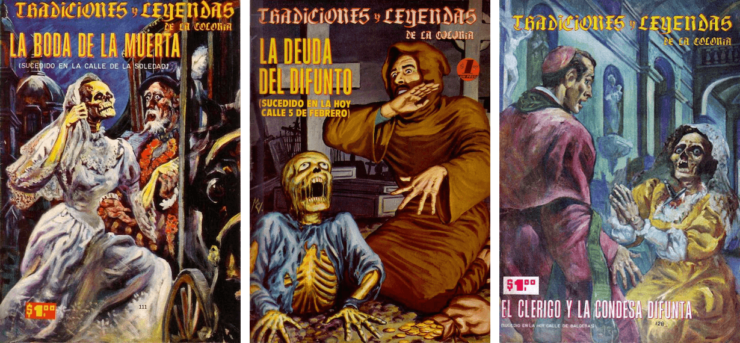

Tradiciones y Leyendas de la Colonia, which began publication in the 1960s, adapted legends and folktales into a comic book format. La Llorona, the Dead Man’s Hand, they were all reproduced with cheap, lurid covers which often featured a woman being assailed by a supernatural foe.

In 1967, following the success of Tradiciones y Leyendas de la Colonia, a rival publisher (Editoral Temporae, later Revistas Populares) launched El Monje Loco. The series had originated as a popular radio serial and had already been adapted in comic book form as part of Chamaco beginning in 1940, so you could say the 1960s release was a spinoff or remake. Each week the Mad Monk of the title would narrate a gruesome story, just like the Crypt Keeper from Tales from the Crypt, and each issue had a color cover and 36 pages of black and white interiors. El Monje was published for 169 issues.

A competitor to El Monje was Las Momias de Guanajuato, published by Editorial Orizaba beginning in the late 1960s. It had a color cover and 32 pages of sepia interiors. The connecting theme was that all the stories took place in the city of Guanajuato, though later on this restriction changed. The comic books introduced La Bruja Roja (The Red Witch) as a counterpart to the Mad Monk and eventually its title became La Bruja Roja. It reached around 150 issues.

In the late 1970s, Editorial Proyección launched Sensacional de Policía and a sister publication Sensacional de Terror, among other titles. Their most popular comics included material scratching the edge of pornography, so it’s no surprise that the covers often featured scantily-clad women, who, as usual, were in danger. Sensacional lasted into the 1980s, enjoying more than 500 numbers. There was also a Mini Terror, published in the 1960s, the “mini” meaning it was a pocket-book comic. There were also Micro Leyendas and Micro Misterios.

Other comic books came and went quickly, including Museo del Terror in the 1960s, as well as Telaraña and Semanal de Horror in the 1980s. There were oddities, such as El Jinete de la Muerte, originally published in the 1970s and reprinted in the 1980s, about a charro (a traditional horseman, somewhat akin to a cowboy) who is handpicked to become Death’s latest messenger. Of course, cowboy-themed comics were extremely popular— this was the era of El Payo, and El Jinete can be seen as a simple attempt to capitalize on that market. It worked, since it actually got a movie adaptation.

Another oddity is a 1960s comic book series following the adventures of a rather ugly, old witch, who with her potions and magic, helps people solve their problems. Originally she appeared in a series called Brujerías which was darker in tone (another Crypt Keeper copycat), but the comic was re-baptized as Hermelinda Linda after Mexican censors deemed it was a bad influence for the reading public. The series veered toward humor at that point. Its off-color jokes made it incredibly popular and it spawned a movie adaptation.

Other humorous comics sometimes included supernatural elements. La Familia Burrón, which followed the adventures of a low-class family living in Mexico City, had a huge cast of side characters, including a vampire, Conde Satán Carroña, his wife Cadaverina de Carroña, El Diablo Lamberto, and others.

More difficult to explain is the existence of El Caballo del Diablo, another anthology comic where the protagonists of each supernatural tale were punished at the end by the devil’s horse of the title.

Probably due to the success of The Exorcist, Mexican horror comics got into the demon possession game with Posesión Demoníaca, first published by Editorial Ejea in 1976, then retitled and republished as Posesión Diabólica and finally known as Posesión. Publicaciones Herrerías had El Libro Rojo, which at one point in the 1980s was one of the most popular comic books in the whole country, only behind El Libro Vaquero and Lagrimas y Risas. While El Monje and Las Momias evidenced a quasi-Gothic look to them and a certain amount of restraint, El Libro Rojo featured much more nudity and salaciousness. It was longer than other comic books, running at 128 pages.

Parallel to all of these comics is El Santo. The masked wrestler and superhero appeared in comics and fotonovelas since the 1950s. His adventures weren’t always supernatural. El Santo could fight criminals and evil wrestlers alike. But the comics did not understand the meaning of genre restrictions, which meant El Santo could also face supernatural foes and monsters.

Spain also generated horror comics, some of which made their way to Mexico. Bruguera, for example, produced Historias para No Dormir in the 1960s and Morbo in the 1980s, which boasted spectacular covers. In comparison, Mexican comic books seemed a bit more lurid and definitely cheaper, no doubt because their audience expected such things, but also because they had a reduced budget.

To take advantage of the interest in horror comics, Spanish editorials not only produced original material, but they translated comic books from other languages. Ibero Mundial Ediciones released Vampus, which compiled issues of Creepy and Eerie. Horror, published by Ediciones Zinco and Ediciones Actuales, translated and compiled issues from the Italian magazines Orror and Cimiteria. From 1984 to 1985 Bruguera published Alucine, which reproduced a German comic book horror series.

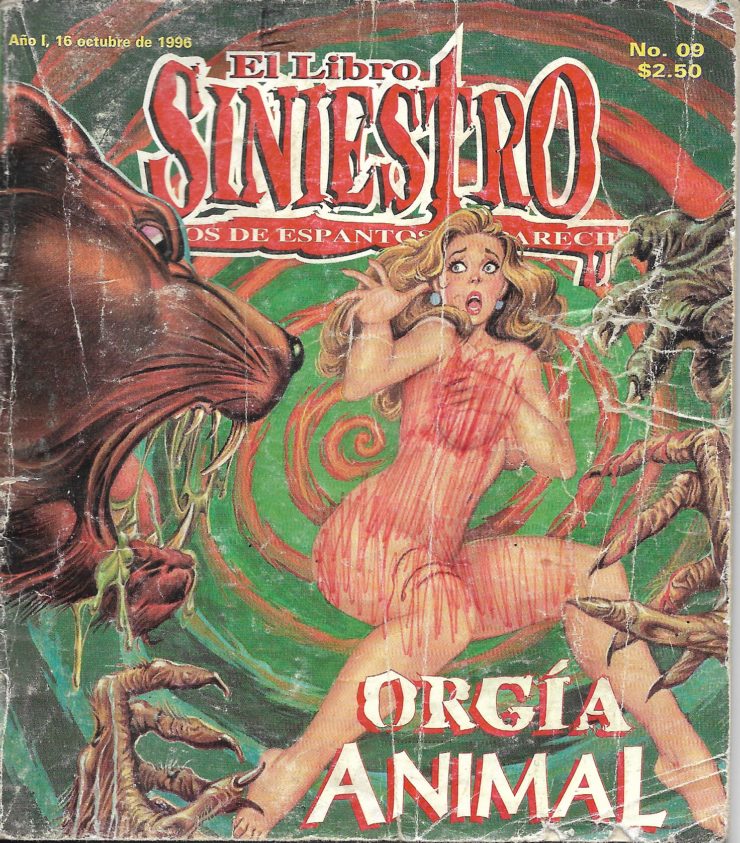

But by the early 1990s the era of the horror comic was coming to an end in both Mexico and Spain. Feeling the pinch, some editorials tried to crank up the eroticism, as was the case with the Spanish Ediciones Zinco, which released Monsters (a translation of an Italian comic book) and Zora la Vampira (also from the Italian). In Mexico, there was a final gasp of horror comics with El Libro Siniestro in the 1990s, which lasted for 168 issues. It was also a highly erotic horror comic book. But this was the coffin closing on a dying industry.

Comic books had flourished because they could provide explicit images and content for people on the move, but the Internet was now allowing consumers to access such content without the need for a flimsy booklet from a newsstand. Plus, there was much more competition from foreign titles, including manga. To make things even worse, Mexico’s paper supply was privatized as a result of the North American Free Trade Agreement. Subsidies ceased.

Nowadays, the comic book industry in Mexico is a shadow of what it was.

Many of the horror comic books from the Golden Age were unsigned or signed with pseudonyms. They were poorly paid work-for-hire and often artists did not want to be associated with them. We do have some names, though: Juan Reyes Beyker, Velázquez Fraga, Ignacio Palencia, Heladio Velarde, among others.

There’s been some interest in the past few years in these forgotten artists. Mexican Pulp Art, with an introduction by Maria Cristina Tavera, collects cover art from the 1960s and 70s. In 2012, the Museo de la Caricatura y la Historieta Joaquin Cervantes Bassoco published Las Historietas de Horror en México, a compendium of horror comic books. Alas, it’s not easily available online.

But what about these comics? Are they worth a look? They’re certainly curious. The art in Mexican horror comic books is often crude, sometimes baffling. There’s an attempt to copy the American art and look of publications such as Creepshow, Eerie and the like. But sometimes the artist veers into originality, either with startling splashes of color or composition. There’s also something gleefully trashy about them and an odd purity to their exploitation. These were not objects to be admired, but to be consumed, and they reflect the dreams and nightmares of an entire era and of a working class.

Thanks to Ernest Hogan for providing scans of comic books from his personal collection.

Silvia Moreno-Garcia is the author of the novels Mexican Gothic, Gods of Jade and Shadow, Certain Dark Things, Untamed Shore, and a bunch of other books. She has also edited several anthologies, including the World Fantasy Award-winning She Walks in Shadows (a.k.a. Cthulhu’s Daughters).

Interesting.

Over here in Germany, when comics are mentioned I think most people think of the “Lustige Taschenbücher” (a monthly series of 250-page-long Walt Disney comic, containing a mix of Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse stories, funnily enough mostly hailing from Italy), as well as maybe “Asterix” which is big here in Europe but probably not that well known across the pond.

I read plenty of Walt Disney comics when I was younger and have a complete Asterix collection but can’t remember having read a single Marvel or DC comic!

Just wanted to say I’m putting this page as a source for my own webpage about Mexican Comics, at least for the horror stuff. https://gutternaut.net/2018/07/la-patria-es-primero-for-the-historietas-of-mexico/

Wonderful history, thoroughly covered and explained. Silvia does not mention other kinds of comics from Mexico, unfortunately. I grew up on those, above all Clasicos Ilustrados, which allowed me to skip many a book assigned on my reading list! There was also another series, about great men, whose title escapes me, which is where I learned who Max Planck was and how he was accidentally poisoned by his maid–who, in an unintentional bit of absurd humor, was drawn as a black woman–in Germany! Institutional racism is hard to escape…

PS Just double checked. Planck really died from a heart attack, so I guess a lot of what I learned from comics was pure fiction. No wonder I became a novelist!

Growing up in the U.S. I was never exposed to Mexican comics, not that I recall. But I somehow escaped the dominance of superhero comics as well. I was always one for the horror comics, usually digests of older stories from Twilight Zone and Boris Karloff titles. But when I was a bit older I was able to get my hands on things like Eerie and Creepy… and it stood out that some of the best content was by European artists… many of them Spanish or Italian.

Too bad there are not big compilations of these older Mexican works, I’d love to see them.

Well, basically with DC and Marvel abandoning newsstands the only comics one can find here in Puerto Rico without going to a Comic Shop are Archie Digests and El Libro Vaquero.

At least you still have comics shop.

Venezuela has become a barren, arid ground for any kind of comics to exist and be sold.

I picked up one of these in the 80s on a family trip to Mexico – the cover was very similar to El Mensajero del Diablo, and it told a story of a young couple who go to an old castle where the boyfriend is (I think?) possessed and becomes a lion-headed werewolf with devil horns and a very buff body. Illustrations were in dark blue ink, no coloring. Wish I still had that!